At present, there is evidence that LGBTQ+ people, whether staff or patients, face specific challenges in health and care. For example, around one in eight LGBTQ+ individuals have reported experiencing unequal treatment from healthcare staff because they are LGBTQ+, and one in seven have avoided treatment for fear of discrimination[1]. However, without effective underpinning datasets, it is impossible to truly understand the extent of these challenges: where they are most pressing, and how to best address them.

In this article, we explain that:

- LGBTQ+ people can face differential health needs as well as experiencing greater discrimination, but the understanding of these challenges is only partial, as a result of poor data availability and quality

- To improve this situation, the NHS should become more purposeful about enabling healthcare providers to collect this data in a considered way, empowering clinicians to do so easily in their patient interactions

- Data availability and quality across minority groups, not just LGBTQ+, is important for understanding the implications of intersectionality

LGBTQ+ people can face differential health needs, as well as experiencing greater discrimination

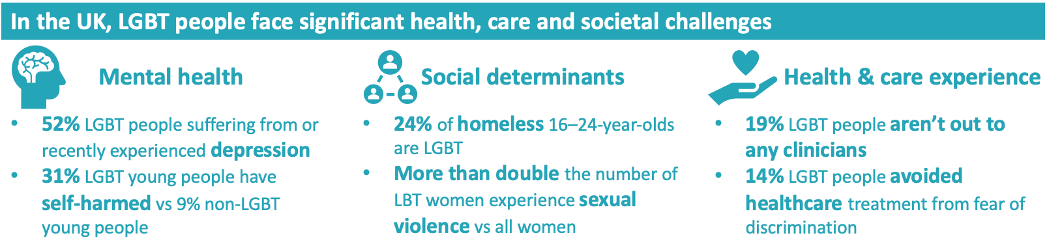

The LGBTQ+ population faces unique health inequalities and discrimination in health and care. We know that LGBTQ+ people are more likely to experience mental health problems, experience homelessness, and experience discrimination in healthcare. For instance, a review of studies on mental health issues in LGBTQ+ communities found gay and bisexual men are four times more likely to attempt suicide across their lifetime than the rest of the population, LGBTQ+ people are 50% more likely to develop depression and anxiety disorder compared to the rest of the population[2]. It is important for healthcare policy makers and provider to be aware of these unique issues to truly meet the needs of the LGBTQ+ population.

Source: LGBT equity in health and care, CF report, 2021

Approximately 20% of LGBTQ+ staff experienced violence from patients or relatives (compared to approximately 14% for their colleagues), the 2022 NHS Staff Survey showed. These figures were particularly high for bisexual and transgender staff. In addition, almost a quarter of LGBTQ+ staff reported to have personally experienced harassment, bullying or abuse from other colleagues. When LGBTQ+ healthcare staff can face such discrimination from their own peers, it begs the question as to whether similar discrimination may exist for patients? Concerningly, 15% of LGBT patients have said they’ve avoided healthcare treatment from fear of discrimination.

The plethora of challenges for LGBTQ+ people in health and care is clear, but most of these insights are from one-off pieces of research. To be addressed effectively, they must first be properly understood in a way which is consistently measurable and provides ongoing actionable insights across the population the NHS serves.

The understanding of these challenges is only partial, as a result of mixed data availability and quality

Good availability of high-quality data on population health matters is essential to ensuring effective provision of healthcare services in ways which meet the population’s needs. The NHS has made recent efforts to improve data relating to LGBTQ+ patients, for example NHS Digital recently published an updated set of Information Standards for sexual orientation monitoring to improve data collection for the Mental Health Services Data Set, in the winter of 2022. It provides the mechanisms for recording sexual orientation of patients and service users above the ages of 16 across NHS health services and Local Authority social care in England. Given the mental health challenges which we’ve highlighted LGBTQ+ people can face, this is a positive development.

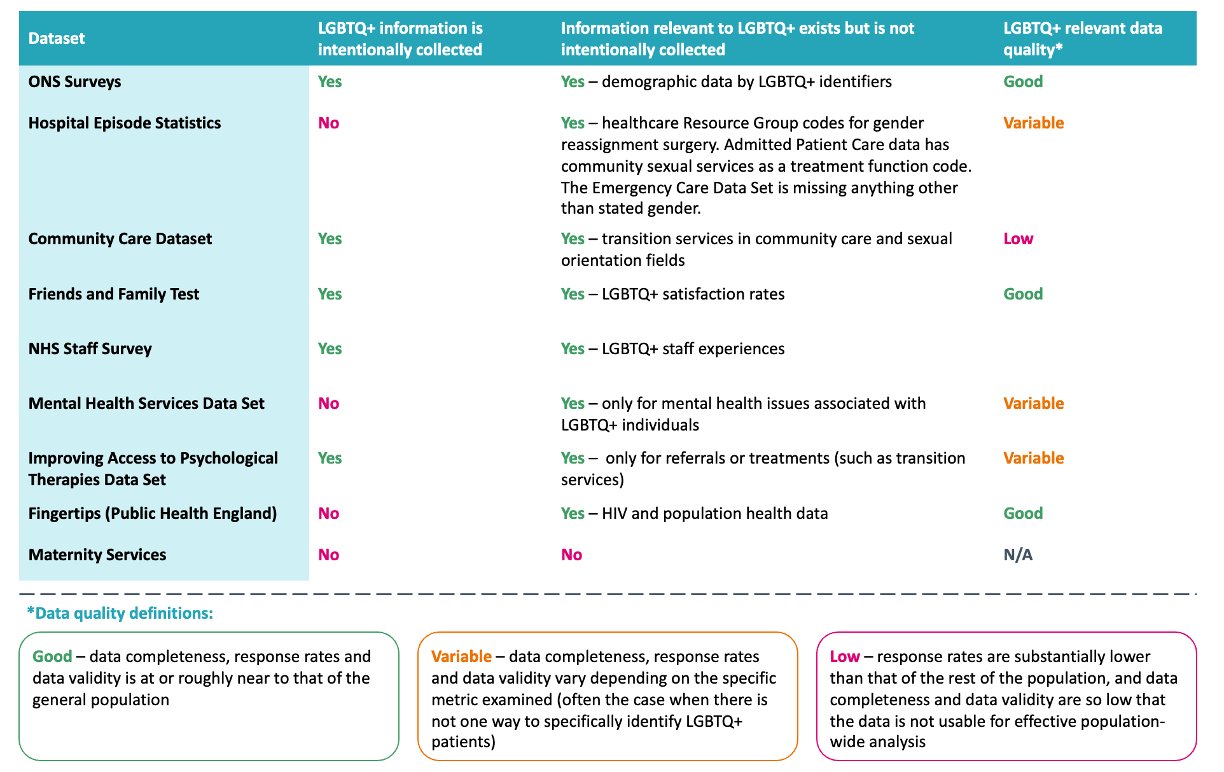

However, NHS data availability and quality for LGBTQ+ individuals are quite mixed and more broadly lacking. Our examination of some key datasets used by the NHS showed numerous did not have any reliable LGBTQ+ identifiers, and of the datasets that do collect sexuality data, the quality is often quite variable.

An overview of LGBTQ+ data availability and quality in some national NHS datasets:

Source: Relevant NHS datasets as described, CF analysis

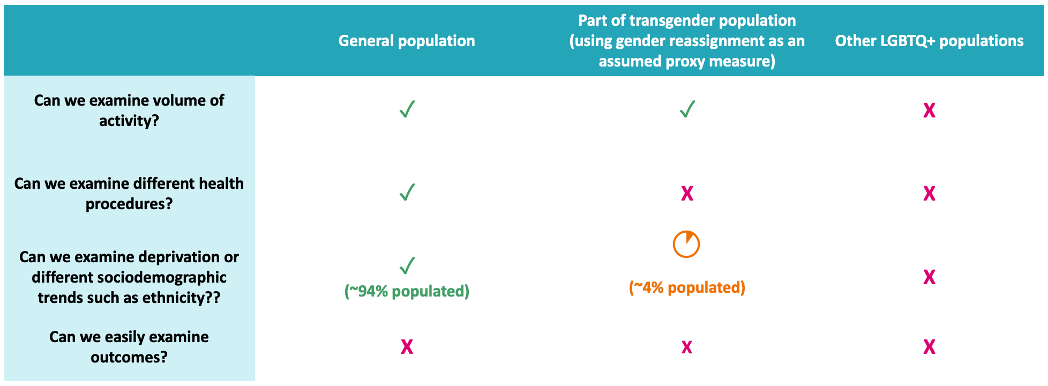

When understanding patient care and outcomes at group and population levels, it’s important to understand other factors which may be present – place of residence, ethnicity, social deprivation and more – and whether these other factors may affect the care and outcomes of patients. This is often referred to as understanding the ‘social determinants of health’. We explored data relating to care which mostly or only LGBTQ+ people use, to better understand how holistically their needs are treated. We used the NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset to explore the last four years of gender reassignments in England, which includes approximately 1,500 procedures.

This is a proxy measure for identifying a portion of the transgender population, but we know that not all transgender people decide to have gender reassignment procedures, and we cannot assume that all people undergoing gender reassignment are transgender either.

For the gender reassignment procedures, demographic data was largely unpopulated, present in the patient records of only 4% of these patients. This is a sizable difference compared to the general population, which has a 94% completeness rate of demographic data. This more generally reflects the difficulty in using such data to create actionable insights: even in those few cases where LGBTQ+ individuals can be anonymously identified for population health analysis through direct or proxy measures, the low quality of the data available makes it challenging to form meaningful insights.

An overview of what can currently be done with LGBTQ+ data using, the HES dataset as an example:

Source: HES dataset, CF analysis

Some LGBTQ+ people may be hesitant to share their data

Compounding the challenges around data quality, evidence suggests that some LGBTQ+ individuals may be hesitant to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity to healthcare providers[3], for a variety of reasons – such as[4]:

- Uncertainty about the relevance of disclosing sexual orientation and gender identity information to the individual healthcare practitioner or the organisation, not understanding whether this information will be important for the clinicians’ diagnosis or treatment.

- Fear over how disclosing this information may affect the patient’s experience and relationship with the clinician.

- Concerns over negative reactions from healthcare providers thereby impacting treatment and outcomes.

This hesitancy is rooted in the reality that LGBTQ+ people have faced in the NHS, with the 2017 National LGBT survey[5] finding 16% of people who had either accessed or tried to access health services had a negative experience due to their sexual orientation, and 38% had a negative experience because of their gender identity. Similarly in a 2018 stonewall survey[6], 13% of LGBT individuals reported that they experienced unequal treatment from healthcare staff due to their sexual orientation and 32% of transgender people received unequal treatment.

Contextualised more broadly, it’s important to remember that LGBTQ+ people have experienced historic discrimination from the healthcare community, such as through blood donation restrictions for men who have sex with men (MSM), which were just recently overturned in 2021. It is understandable that the combination of historic and present-day disparity in experiences could prevent a proportion of LGBTQ+ people feeling completely able to disclose their identity without fear of discrimination in some form.

Our understanding of some people’s experiences is also limited, as surveys and data collection more often focus on lesbian, gay and sometimes transgender people than bisexual, queer and other identities . Not only can this negation of some data points result in information that is unreliable – as people may have to resort to just picking the identity that most closely conforms to their own, or possibly choose to not respond at all – but it may also unintentionally lead to unsystematic and biased data.

Finally, the collection and storage of data around sexual orientation and gender identity – a sensitive matter for many individuals, especially those who may not be ‘out’ to everyone in their personal life – may raise concerns about individuals’ privacy and security. This only multiplies any impact that healthcare providers unintentionally disclosing this information due to mistakes or negligence might have and could contribute towards people’s hesitancy to share aspects of their personal identity.

With better data collection, more informed decisions could be made on improving healthcare experiences and outcomes for LGBTQ+ people

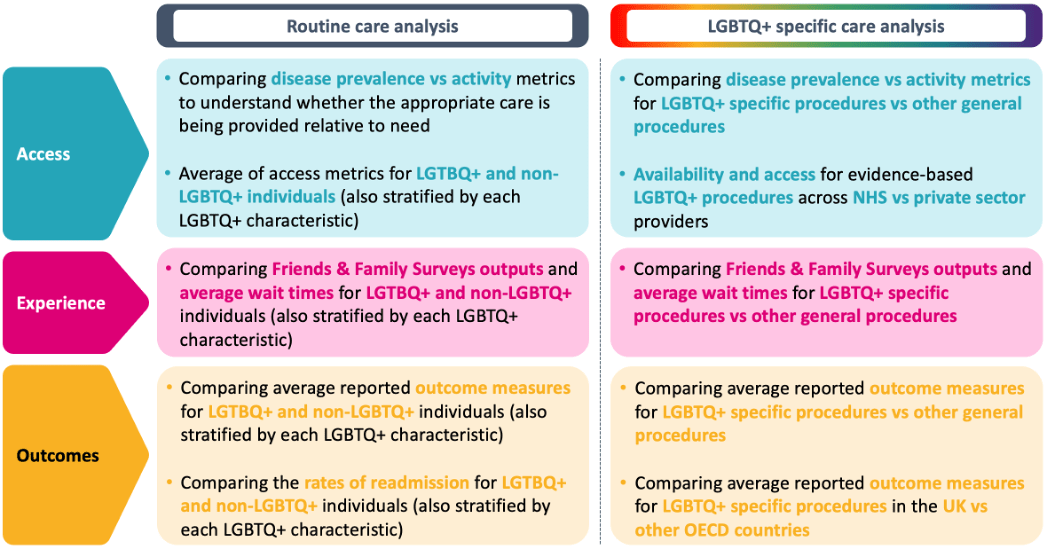

In an ideal hypothetical scenario, if any data relating to LGBTQ+ people we wanted was fully available and high quality, we could develop analysis to understand whether the needs of LGBTQ+ patients are being fully met and identify any health inequalities which exist, by exploring metrics around access to care, experiences of receiving care, and outcomes following care. A deeper, data-driven understanding of the issues in this area would also enable increased awareness, identification of root causes, and development of targeted initiatives to address any challenges.

We have outlined example analyses that could be undertaken to understand these disparities in access, experience, and outcomes – considering both routine care (that care which all people in the general population could receive) and LGBTQ+ specific care (such as gender reassignment procedures or certain sexual health services).

Examples of some analysis which could be undertaken if LGBTQ+ data was readily available and of good quality in NHS datasets:

To improve this situation, the NHS should become more purposeful about enabling healthcare providers to collect this data in a considered way, empowering clinicians to do so easily in their patient interactions

Broadly speaking, NHS care is generally provisioned based off measured need for population demographics and patient cohorts, but it can be difficult to measure the needs of LGBTQ+ people reliably. Having the right data available in healthcare records is therefore essential to addressing matters like LGBTQ+ health inequalities, as these could then be continuously measured in a standardised way, monitored for changes (hopefully improvements) over time, and allow healthcare providers to tailor their offering to these patients’ specific needs where appropriate. The NHS should therefore aspire to accurately collect more LGBTQ+ healthcare data moving forwards.

We’ve also reflected on the nuanced considerations that must be reflected on if LGBTQ+ healthcare data collection is purposefully grown in the future. The NHS should purposefully consider these points and more, to ensure that any actions taken in this space with the best of intentions for LGBTQ+ people do not advertently lead to situations which risk eroding LGBTQ+ people’s trust, from the patient-to-clinician level through to the population-to-health-system level.

In reality, this involves providing the right data infrastructure to healthcare provider organisations – such as fields in electronic patient records to record the relevant information – and empowering clinicians to record this information easily, in part by training them on how to practically record the information, and in part by supporting them to know how best to have conversations with patients about their sexuality and gender identity.

Data availability and quality across minority groups, not just LGBTQ+, is important for understanding the implications of intersectionality

Understanding other protected characteristics – such as ethnicity – also plays a role in deepening our understanding of LGBTQ+ patients’ care, as discussed already in relation to gender reassignment procedures. This is because evidence on the social determinants of health shows that intersectionality of identity – such as being gay and from an ethnic minority – can affect your health too. Therefore, ideally data on ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, disabilities, and more would also be fully available to enable greater insights from analysis in the future.

Seeking more food for thought?

If you want to learn more about the experiences of LGBT patients and staff in healthcare, read our 2021 thought leadership report

“LGBT equity in health and care”.