Addressing access and adoption of medicines in the UK is crucial for the UK to deliver on its Life Sciences vision, and ensure patients receive best quality care

The UK pharmaceutical industry – revered as a global leader following development of the world’s first COVID-19 vaccine – stands at a pivotal moment. Despite boasting a world-class scientific community, a respected regulatory framework, a single payer national healthcare system, and a promising national dataset, investment by global Pharma companies is declining. This protracted decline has spread to industry clinical trial activity, especially in late-phase clinical research. Since 2017, recruitment to trials has fallen by 27%, the number of Phase III clinical trials has declined by 32%, and the UK’s global ranking for Phase III trials has plummeted from 4th to 10th. Late-phase clinical trials are critical to broadening UK patients’ access to research (because they recruit the largest cohorts) and increasing adoption and uptake of new medicines and vaccines into routine care (because the research has been carried out within the healthcare system).

This stands in sharp contrast with the Labour government’s aspiration to make the UK a global Life Sciences superpower, with funding promised to support growth, especially for the the NHS and clinical trials. However, medicines discounts and rising industry rebates have long been cited as eroding the attractiveness of the UK market to pharmaceutical companies. Even if the lower pricing in UK was accepted, this is compounded by slow access to new medicines at the health system level; with adoption falling short of NICE estimates of addressable population within a drug’s commercial lifetime. Pharma companies are also expected to navigate hurdles in place to contain NHS spending on medicines, notably budget impact tests, managed access agreements, possible therapeutic tendering, as well as the cost of submitting a dossier to NICE.

These challenges threaten the UK’s position in the global Life Sciences sector, and also the ability of the NHS to provide optimal patient care. This could result in fewer innovative therapies being made available to patients, as market conditions render them commercially unviable or NICE deem treatment to not be cost-effective. This in turn could result in worsening health outcomes and a compounded lag in the uptake of innovative therapies resulting in an outdated standard of care unfit as a comparator for new therapies in clinical trials.

The Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing, Access and Growth (VPAG) provides hope of strengthening the UK’s competitiveness in health and Life Sciences to drive innovation-led growth. This new agreement for 2024 sets the size of the NHS medicines budget for the next 5 years, with the new deal set to save the NHS £14 billion over the timeframe by continuing to restrict NHS expenditure on new medicines. However for Industry it offers a higher growth rate of 2% (nominal per year), up from an allowed growth rate of 1.1% previous to this, before further rebates kick in. This is achieved through a sharp differentiation between newer medicines, only originator medicines and their licensees, and older ones, including branded generics and off-patent originals, being subject to mandatory payback rates of 11.6-16.5% and 10.0%-11.0% respectively (from Q3/4 2024 to 2026 onwards).

Through the O’Shaughnessy review, an independent review in early 2023 into commercial clinical trials in the UK, the then Conservative government agreed to implement all 27 recommendations, categorised into five headline commitments over the following two years. By increasing the promise of later-Phase trials in the UK, global Pharma companies gain experience of the UK health system and patients, potentially offering some advantage when submitting applications to NICE for cost-effectiveness.

These developments: regulatory change, development of data environment, VPAG and commitments to improve trials set the stage for a strong Life Sciences sector. But to realise this potential will require medicines to see rapid uptake in the UK once they have passed the triple test of regulatory approval (MHRA), cost-effectiveness (NICE) and reimbursement/pricing (NHSE) to adopt a stance that these evidence-based and cost-effective interventions should be adopted as widely and swiftly as possible within guidelines established by NICE to maximise patient outcomes and cost effectiveness.

There are significant barriers to uptake of medicines in the NHS, in all care sectors and commissioning routes

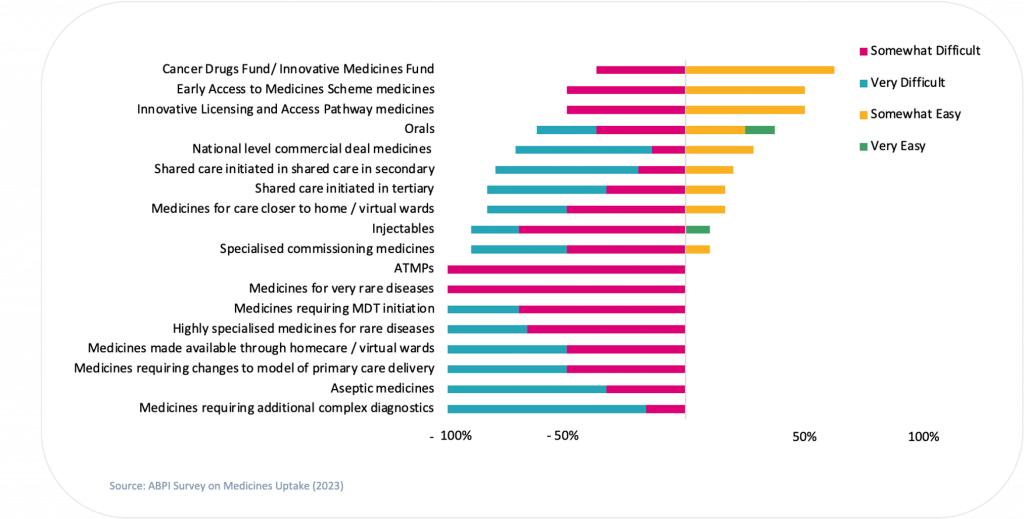

Over the last two years, CF has been working with NHS England and Life Sciences partners to better understand the issues around slow access to and adoption of new medicines at all levels of the healthcare system. Our analysis demonstrates there are significant barriers to access and adoption in the NHS, across all care sectors and commissioning routes (see Figure 1 for industry experience with various medicine archetypes).

Figure 1. Degree of uptake difficulty that Industry survey respondents experience with different access schemes and treatment types

In primary care , we found:

- Prescribing at primary care requires addition to local formularies – a duplicative approval process

- Primary care clinicians lack confidence in prescribing new and innovative medicines when there are no specialists (for example in secondary or tertiary care) already prescribing them

- GP practices are highly variable in management, policies and working and this can all impact rates of access and adoption

In secondary care we found:

- New medicines often require complex changes to care pathways, yet these adjustments are often overlooked in planning ahead of commissioning

- Prescribing may be contingent on clinic or MDT initiation, which entails discussions of complex patients or new diagnostic pathways. This may lead to delays in initiation or require extensive clinical pathway and change management planning

- In second or third-line medicines, pathway design often prioritises optimising first-line treatments initially. Consequently, there is a delay in considering, prescribing and utilising second and third-line medicines

At the tertiary level we found:

- Tertiary care medicines are typically high-cost and require specialised commissioning. This can delay to access and adoption of innovations

- Access to tertiary care medicines is only permitted through designated specialist providers. Determining which centres a medicine can be prescribed at and accessible to patients can delay commissioning and access

- Many of the issues encountered with secondary care medicines, such as pathway complexity and waiting lists, are exacerbated in tertiary care, leading to additional delays in access and adoption rates

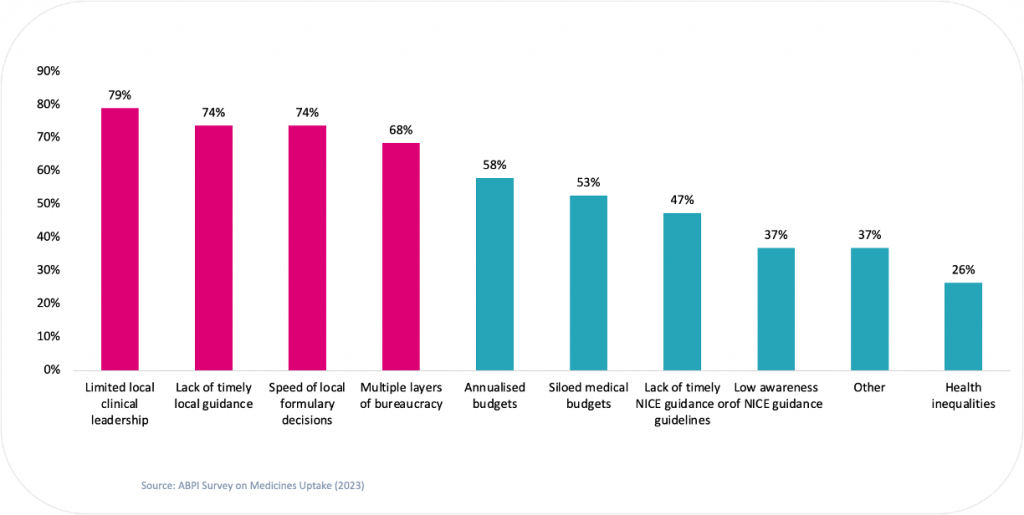

Moreover, our analysis also revealed that limited local leadership was the most common perceived reason for poor uptake of NICE approved medicines amongst Life Sciences companies.

Figure 2. Percentage of survey respondents that believe each factor to be limiting better uptake of NICE approved medicines

Uptake barriers across commissioning routes

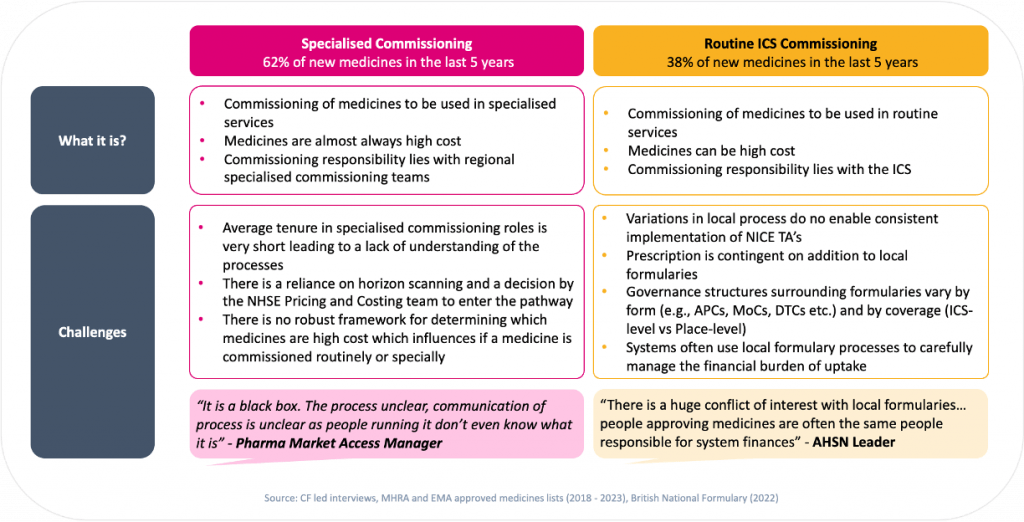

The method of commissioning a new drug can also impact the rate of access and adoption.

Figure 3: New medicines can be commissioned via specialised or routine commissioning – each present their own challenges

Our research showed that specialised commissioning, overseen by regional specialised commissioning teams, can be hindered by unclear processes and a general lack of understanding amongst both the staff involved and for pharmaceutical stakeholders.

Routine commissioning, managed by local ICSs, required adding the new drug to local formularies. This is in effect a duplicative approval process – if there is no local “business case” for the addition of the innovation, based on population need versus the cost of the drug itself, the medicine is simply not added to the formulary. This may lead to conflicts of interest, as ICSs often use local formulary processes to carefully manage the financial burden of uptake.

The recent devolution of specialised commissioning from the NHS to Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) has significant implications for health systems and the Life Sciences sector. The aim is to foster closer collaborations between Pharma companies and ICSs, enabling a better understanding of local healthcare needs and the development of tailored solutions. However, it also introduces challenges such as fragmented decision-making processes and varying priorities across different ICSs. The devolution process may lead to more efficient decision-making and quicker approvals for new medications and treatments. Conversely, Pharma companies might face operational complexities and increased costs due to the need to navigate different procurement and formulary processes. Whilst the devolution of specialised commissioning presents opportunities for customised healthcare solutions and market expansion, there is a requirement for careful management to address associated risks and ensure a smooth transition to support ICS clinical strategies and operating models.

Across all care sectors and commissioning routes, some common themes emerge that provide background context as to why the uptake of new medicines is so slow in the NHS:

>>There is a lack of clinical leadership amongst frontline professionals

In general, frontline NHS clinicians are less familiar with new medicines, therefore a confident prescribing narrative is often missing amongst clinical leaders. The channels for prescribers to learn about new medicines within the NHS are poor, and there is clear demand for greater guidance around implementing new treatments. NICE guidelines also do not consider the cumulative impact of drug treatments, and may not live up to practitioner expectations.

Encouraging clinical leaders to prioritise patient engagement and education could enhance access, adoption and outcomes, by promoting better adherence to drug regimens and reduced patient attrition rates.

“The NHS does not have capacity to train clinicians on latest clinical advances. External experts step in to do the education.”

– Director, Pharma

“Traditionally, national programmes have been sioled and focused purely on NHS issues, hindering the ability to effectively engage national clinical leaders on guidelines and medicines uptake matters.”

– National Specialist Advisor, NHSE

“NHS bodies could support work around NICE updates of guidelines which take a long time and slows progress.”

– Director, Pharma

“The prospect of guideline updates does risk introducing further review of medicines already approved after the fact.”

– Director, Pharma

>> The local commissioning and management of new medicines is inefficient and ineffective:

As mentioned previously, local formularies are used by ICS commissioners to control the availability of new medicines based on the viability of the local business case. This slows access and adoption, and can lead to a postcode lottery where some patients are able to receive a drug in some parts of the UK, and others who are based elsewhere cannot. However, if a new medicine has received a positive NICE approval, there should be automatic formulary inclusion for the new medicine. Whilst there may be a short wait for a committee meeting for inclusion to be agreed in some ICSs, and the need for a push by clinicians in others, NICE approved medicines should not be subject to another round of formulary decisions at the ICS level. Regional Medicines Optimisation Committees (RMOCs) also appear to have little-to-no impact on this process or the uptake of new medicines and innovations generally.

In addition, data isn’t optimised to anticipate and understand the adoption of new medicines and innovations. Implementation costs may exceed the cost of the medicine itself, and may not be planned for. These costs are not forecast by the NHS and so the process of approving medicines stands separate from long term NHS budgeting. For instance, we can now envisage challenges in obesity and dementia costs likely running ahead of expectations. This means that funding mechanisms may not cover the whole cost of adoption – which can also stall uptake.

“New drugs often take a long time to be included in local formularies leading to poor uptake, despite legal precedence for uptake within the mandated time period. RMOCs do not influence inclusion of drugs to local formularies.”

– National Specialist Advisor, NHSE

“Addition to local formularies acts as a blocker to adoption of new medicines. Despite a mandate that requires adoption post NICE, many second-guess NICE. RMOCs role is unclear and they have no influence on formularies.”

– Access Manager, Pharma

>> The complexity of the NHS system as a whole impedes uptake

The NHS system as a whole is very complex, and this presents challenges in terms of supporting market access:

- Complex pathways: access and adoption of new medicines usually takes place across many different pathways

- Complex advice: there are multiple different forms of guidance on medicines use, and these often do not align with one another (NICE commissioning mandates, NICE guidelines, NHSE guidelines)

- Divided accountability: different organsiations take the lead on different parts of a pathway, but without clearly defined accountability

- Lack of NHS understanding: high staff turnover rate in NHS bodies that support new medicines through the pathways results in a poor understanding of the processes by NHS staff that are assisting Pharma navigating the complexities to access at all levels of the health system

“It is a black box. The process unclear, communication of process is unclear as people running it don’t even know what it is.”

– Market Access Manager, Pharma

“NICE implementation team could help to unlock many barriers and remove duplication of work instream and upstream.”

– TA Committee Member, NICE

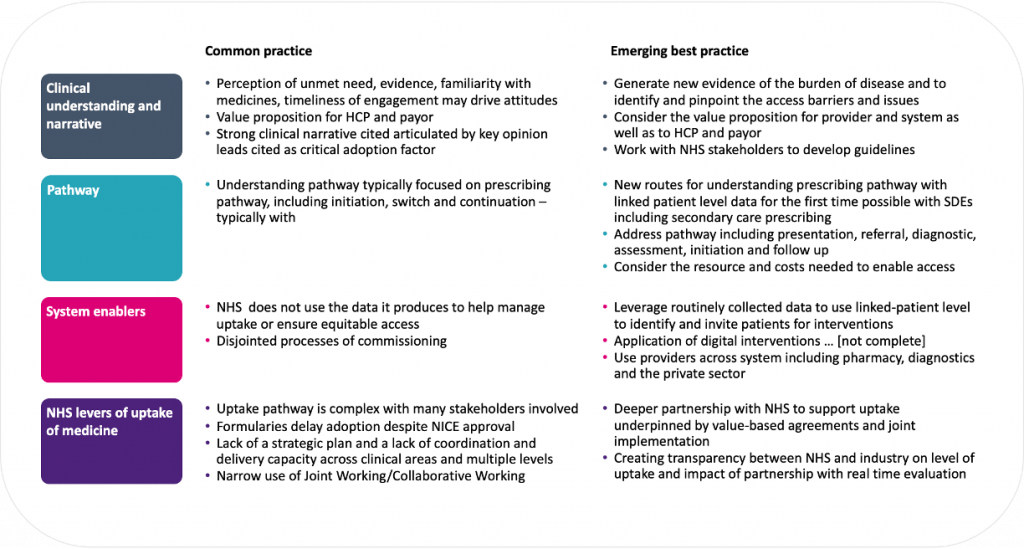

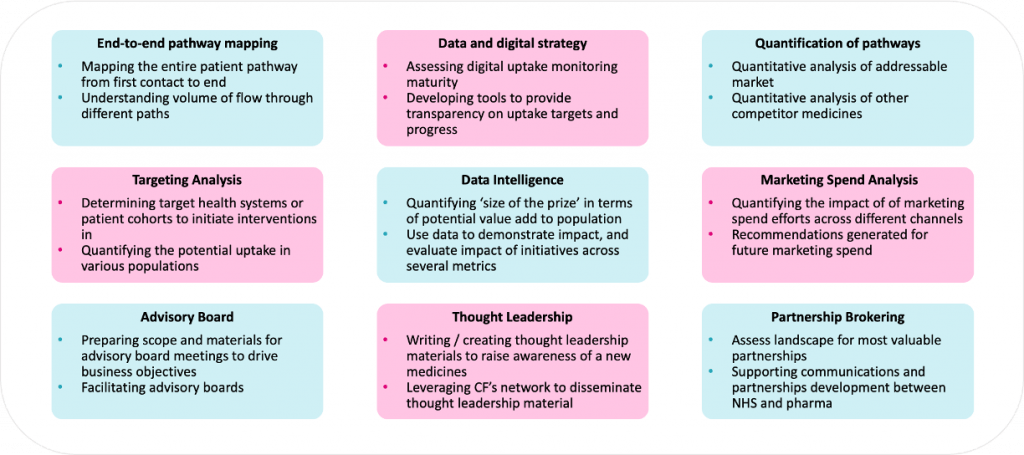

Through our experience, we have evaluated common practices and defined a list of emerging best practice and formulated into a framework to address these barriers, accelerate uptake, guide planning and market shaping, which we routinely use in our work with clients

Figure 4: Levers to support access, adoption and market shaping of new medicines and innovations

Conclusion

We are now at a pivotal juncture where we can address the causes of low rates of access and adoption and build an impactful, respectful and enduring relationship between the UK health system and the Life Sciences industry. As a trusted partner to both sectors, CF is committed to supporting Pharma in understanding and navigating the pathway to innovation uptake.

Leveraging our therapeutic area expertise and in-depth understanding of pathways and processes, underpinned by healthcare system data, we use a highly collaborative approach. We engage clinicians, payers, health system stakeholders, patients, and regulators prior to launch and find ways to align the needs of the health system with Pharma’s objectives and solutions based on evidence. Our goal is to support rapid access to innovation and support the development of new services that improve patient outcomes and support sustainable healthcare.

Figure 5: A range of interventions that can be used

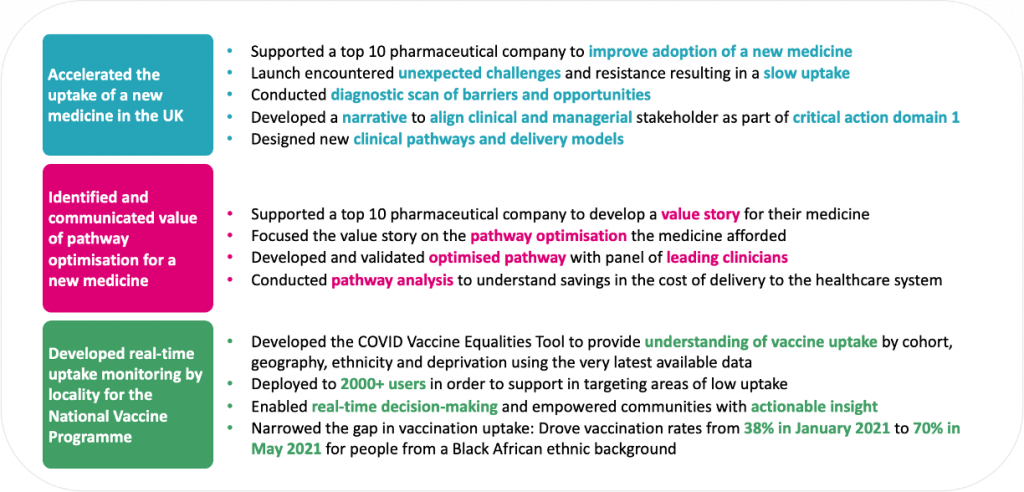

Selected examples of our approach working across a range of launch scenarios

Please contact us today to find out more about this article and our work across market access.