What will it mean to improve outcomes for lung cancer patients?

Every four minutes someone in the UK dies from cancer, since the early 1970’s mortality rates for all cancers have decreased by 17% in the UK, yet there are still unnecessary deaths each year. Over 363k patients are diagnosed with cancer each year; c. 47k of those cases are caused by lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in the UK, with over 47,000 cases each year and 35,300 deaths every year within the UK, that’s 130 new cases and 97 deaths each day. 79% of lung cancer deaths are preventable, but unlike other cancers which may detected through visible changes to the body or can be felt, lung cancer is often found late when it’s metastasised in Stage III or Stage IV when survival rate is just 40% and 20% respectively.

There are four key changes needed to improve lung cancer outcomes:

- Increase early diagnosis

- Reduce the geographical variation of treatment rates

- Improve the time to treatment

- Increase the adoption of novel approaches and treatments.

Increase early diagnosis

In 2018, the Conservative government set out an ambition to improve cancer survival as part of the LTP, which for lung cancer would increase the early detection rate from one-in-four to three-in-four by 2028. Then Prime Minister, Theresa May remarked “This will be a step-change in how we diagnose cancer. It will mean that by 2028, 55,000 more people will be alive five years after their diagnosis compared to today.”

Lung cancer is at its most devastating when it spreads rapidly throughout the tissue, making surgery an impossible as the lungs are littered with small tumours. Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy have been the most effective at shrinking the tumours and is used in percentage of case eradicating the cancerous tissues. If we were to deploy drug therapy in Stage I or Stage II lung cancer it would reduce the number of radiotherapy or chemotherapy sessions required, effectively eradicating cancerous tissues in 59% in patients.

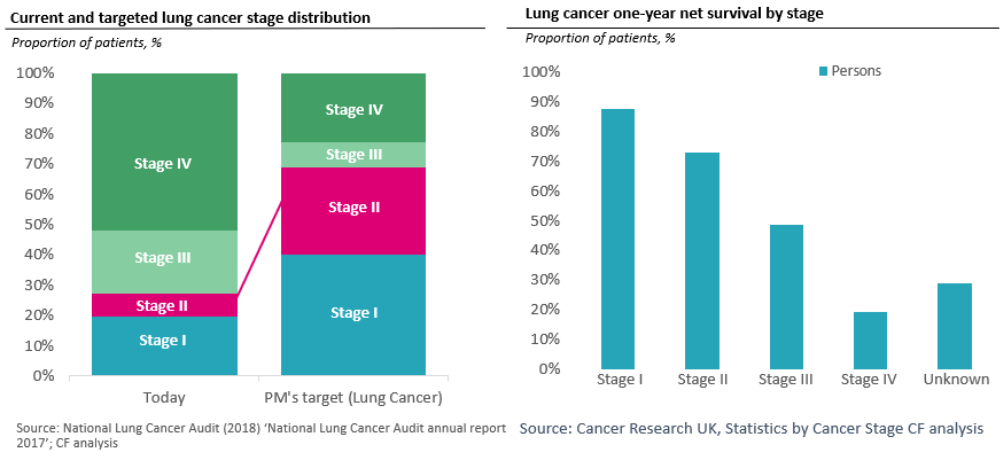

As shown in the data, the majority of lung cancer cases are diagnosed in stages III and IV (70%), yet we know that a person diagnosed at stage IV has just an 19% survival rate after the first year in comparison to stage I cases who typically have a one-year survival rate of 88%. When looking at the five-year net survival rate the prognosis becomes more dire, stage I patients have a 57% survival rate in comparison to just 3% for those with stage IV. Unfortunately, 70% of emergency presentation cases (stages III or IV) are via Accident and Emergency.

Reduce geographical variation in treatment rates

The 2010-14 period showed considerable variation across geographies, which was associated with survival rates. It is evidenced that lung cancer effects those in the North East and North West of England, more so in than in other areas of the country, 20% of all cases in 2012 came from these two regions, as the cancer disproportionately affects those with an lower social-economic status. Men and women who were classified as ‘most deprived’ were at great risk for lung cancer (2.5 greater for men and 2.7 times greater for women). Even once cancer is detected there is then significant variation in treatment rates across geographies ranging from 55% to 65% treatment rate across all stages of lung cancer.

Combining the impact of these two changes we would see the following:

| Distribution Now | Distribution By 2028 | Treatment rates Now | Treatment rates by 2028 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 19% | 39% | 74% | 81% |

| Stage II | 7% | 28% | 74% | 81% |

| Stage III | 20% | 8% | 69% | 76% |

| Stage IV | 50% | 22% | 51% | 56% |

Improve time to treatment

None of England’s Cancer Networks reached the 62-day waiting target of 85% (from urgent referral to treatment) when combining the last 4 quarters. Even short delays in receiving treatment could have a negative impact on patient outcomes; it takes less than 10 months to progress from stage I to III. Hence there is now a move to short the time to treatment further.

Increase adoption of novel therapies

A crucial step in making earlier detection worthwhile is to ensure therapies are available. There is now an exciting promise of potentially curative treatment as immunotherapies recently emerged an innovative treatment option for several cancers. They represent the most promising new cancer treatment approach since the development of the first chemotherapies in the 1940s.

Manchester Lung Health Check demonstrates how the adoption of novel approaches can improve diagnosis rates.

In 2014, the University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, launched a pilot led by MacMillan. Adults aged 55 to 74 across 14 GP practices were invited to book a Lung Health Check, regardless of whether they were a smoker or not. The health check units were based in supermarket car parks to make taking part accessible and convenient. A lung specialist nurse conducted the assessment which included a discussion about symptoms, a breathing test and a calculation of a person’s individual lung cancer risk. Anyone at high risk of lung cancer was invited to have an immediate low-dose CT scan in a mobile scanner in the same location.

- 2,500 people attended

- Over half of the attendees were eligible for a CT scan

- 42 people were found to have lung cancer

- 80% of those were either Stage I or Stage II (national average 26%)

- 90% of those diagnosed were offered potentially curative treatment (national average 74%)

This exciting development has been heralded by the Long-Term Plan as the future of lung cancer early detection and one that should be broadened across the country.

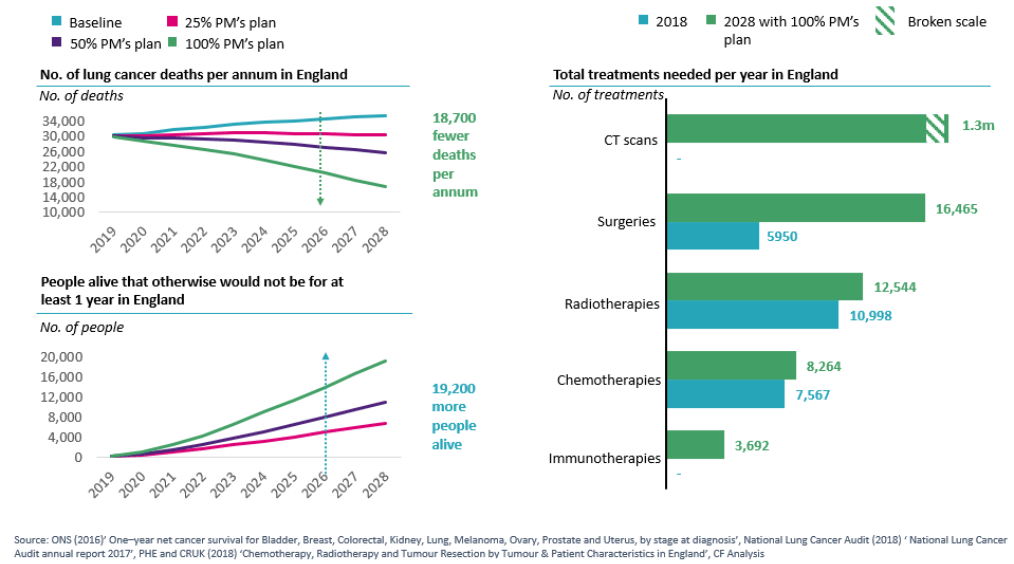

19,200 lives

Our analysis suggests that combining all four levers outlined above would result in 18,700 fewer deaths from lung cancer could be avoided per annum, resulting in 19,200 people alive who otherwise would not be for one year. This would be an astonishing achievement and that would take substantial effort to meet. To work out what it would require we modelled the likely impact.

To achieve 75% of the population being diagnosed in stage III or IV amongst the 50-75 age group, our analysis shows that 1,3 million low-dose CT scans will need to be conducted every year. Our estimate is that this would require 74 additional CT scanners which needs additional investment in staff members to operate the machinery for 9 hrs per day, 365 days a year. The analysis in the above chart shows that surgeries would need to more than triple, requiring additional surgical teams and surgical theatre time to accommodate the increase in surgeries. And in addition, there would be the need to introduce immunotherapy

These are huge numbers, but so, too, are the numbers of the potential impact. Based on the current GVA of the current UK workforce we can infer that should all 19,200 persons of working age (18-67 years), and all of whom are able to work then in the first year would result in £859m in economic benefit from avoided deaths. If we take the five-year survival rate for stage I cancer (57%), there would still be a £490m economic benefit to the UK.

Moving forwards to deliver significant outcomes for patients

This is clearly a bold clear benefit to both the population and the NHS itself. For any particular area to implement this it would need to consider how patients will be screened, how access to low dose CT scans will be provided and then interpreted, how will the increased surgical capacity be handled, and how will immunotherapy be introduced? Beyond considering pure capacity there is a need to consider how this would be commissioned and how the relevant partners in any area can come together to address this, supported by the national NHS.

We cannot afford to delay the opportunity to improve patient outcomes, not only can we save 19,200 lives, but we can contribute £859m back to the economy.