In recent years there has been increasing discussion surrounding reform to the social care delivery model and the mechanisms through which is it funded. As our population continues to age and grow the weight of pressure builds to ensure there is a sustainable, equitable and fit-for-purpose system in place. The Dilnot Commission on Funding of Care and Support established by David Cameron’s coalition government in 2010 published their recommendations in July 2011. The Dilnot report found that the current social care system was inadequately funded, delivered inconsistent services, was not fit for purpose for the 21st Century and was in dire need of reform1. Our analysis of local authority data from 2018/19 found a 38% point difference in proportions of care provided at home across different councils in England.

Since 2010/11, the years of austerity meant a decrease in the total spent on adult social care in real terms, when adjusting for inflation, over the 9 years leading to 2019-20. This was despite increasing demand for services year on year2. 2019/20 was the first year since 2010/11 to have spent more, seeing £99m above the 2010/11 levels, representing a 0.4% increase on the figure 9 years previously3. The population of over 65’s grew by 2.3million or by 23% in the same period4. In his first speech after becoming Prime Minister on 24 July 2019, Boris Johnson told the nation: “We will fix the crisis in social care once and for all with a clear plan we have prepared.”

After an incredibly challenging year responding to Covid-19, fundamental reform of the social care system is needed to address the longstanding issues in social care exacerbated by the pandemic. In the last year, local authorities and their social care providers have struggled with a devastating number of care home resident deaths, coupled with inadequate PPE, personal protective equipment, and challenges with staff sickness and isolation. By 19 June 2020, there had been more than 30,500 excess deaths among care home residents in England and data from the first pandemic peak showed social care staff were around twice as likely to die from Covid-19 as other adults5.

One of the benefits of the pandemic has been the close working across the health and social care system at a local level, with some of the historic bureaucratic barriers removed such as seen by the Covid-19 COPI, Control of Patient Information, legislation6. However, there is no doubt that the discharging of patients into care homes in the first wave enhanced the spread of Covid-19 through the sector, and local authorities we have spoken to have shared their concerns about acute NHS staff deciding the best location for individuals on their discharge from hospital. Advancing our social care model might instead be best served by listening to the people in receipt of those services and our local communities delivering the services.

As we look forward to what a potential new model for social care may look like, we have reflected on the ‘Home First’ approach, pioneered by the Local Government Association in partnership with NHS England7. Despite great successes in many parts of the country, a recent report written and published by the IPPR, Institute for Public and Policy Research, explores the discrepancies of social care provision at home across the country. The report identifies key social care challenges and highlights the opportunity to support more people in their own communities rather than in nursing or residential homes, thus, reducing the total cost of care and retaining people’s independence.

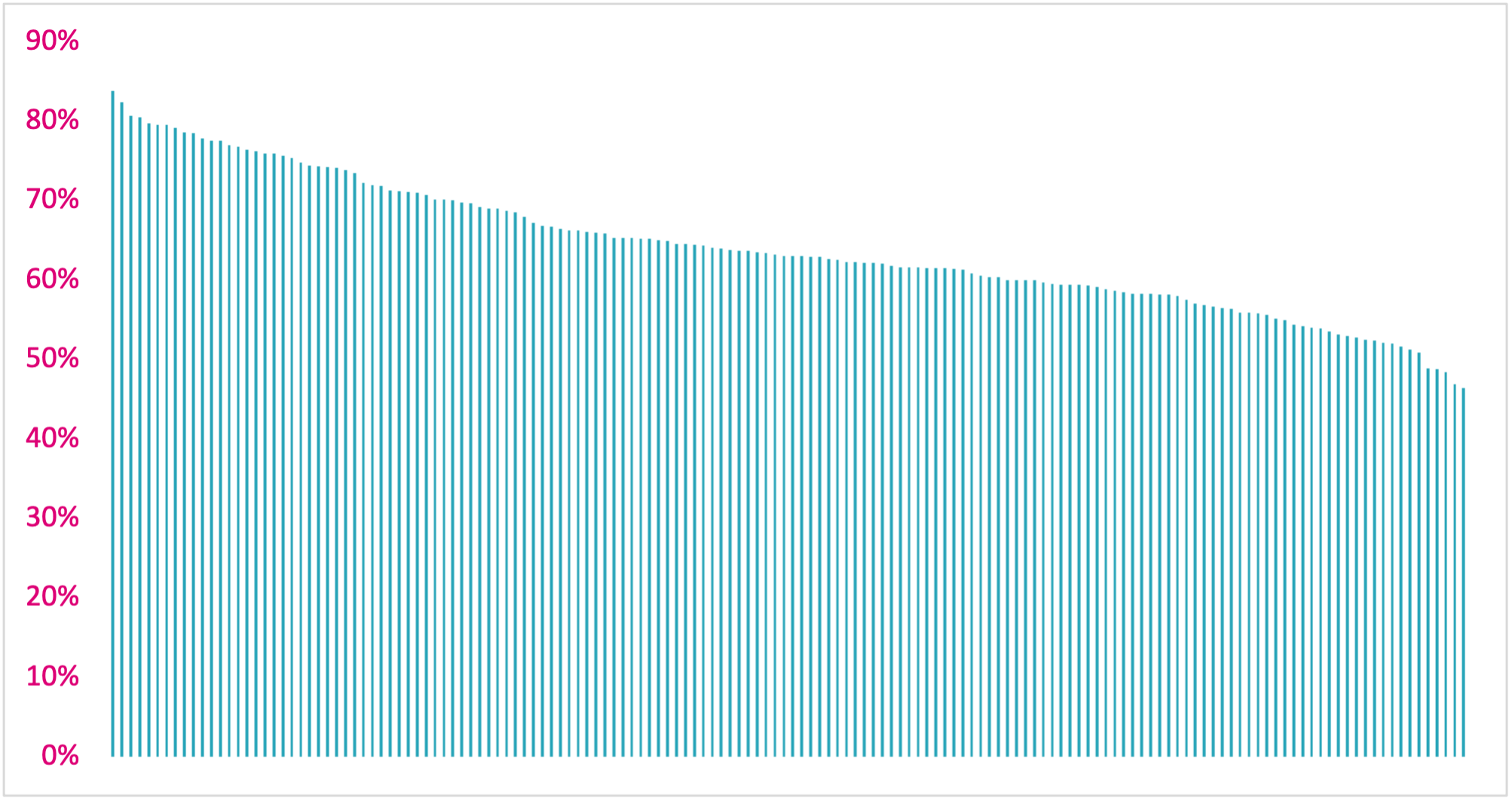

There are many ways in which local authority, community health, voluntary services and informal carers support people to stay in their communities, allowing them to retain their independence and creating a more personalised care package. Admission into a care home involves moving a person away from their home and familiar surroundings, and in some cases, a distance away from their families. Our analysis, Figure 1., shows that the proportion of care provided at home varies across different councils – from as low as 46% to as high as 84%.

Figure 1 The variation in proportions of care provided at home across different councils in England – from 46% to 84%.

There is a substantial opportunity to keep citizens in their own homes by reducing the variation between authorities and levelling up the proportion of care delivered at home compared to in a care home. Our research, published in full by the IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, shows that if all authorities were able to match the top quartile in comparable authorities this would mean up to 80,000 more individuals across the country able to stay in their own homes each year. This translates to an annual social care budget saving of £1.1billion with a further potential £1.6billion saved by the NHS through improved discharge procedures.

In our work supporting health and care systems to design care pathways that enable people to both remain well and help those who need help to retain their independence, we have been struck by the personal stories that sit behind each statistic. Choosing how best to support a loved one is never an easy decision for any family, with requirements to balance costs, the safety of their relative and the wishes of the wider family and most importantly the individual. Placing a family member in a care home often means selling a long-standing family home in order to fund the care and places significant financial burdens on families1. Sometimes the care home placements available are far from family and an individual’s community and social lives, which can be very unsettling and can exacerbate the loss of independence and worsen a person’s functional level. Around 90% of people would rather be cared for in their own home with support rather than being placed in a residential home, should the need arise8, however, the evidence suggests your chances of either outcome depend on your postcode.

For many health and care systems, as well as the personal cost to the individuals being cared for, caring for people in a care home rather than at home can come with increased costs for the system as a whole. Providing reablement services at home is believed to reduce ongoing care costs for local authorities9, and individuals who are independent are more likely to stay well than those admitted to care homes. Many people are admitted to a care home following a hospital stay, often following a series of assessments in hospital. Our work has found that on average it takes over four times as long to discharge a patient to a care home than it does to discharge a patient to their own home, increasing the length of stay for that person in hospital and again increasing costs for the system.

Local recommendations

Alongside reformation of the social care model at a national level, there are some steps that local systems can take to help best support people in their own communities and homes.

- A Population Health Management approach is crucial to developing a care model for an ICS or a place, to identify the needs of the local population at a neighbourhood level. This allows for the design of personalised services and pathways that will keep people at home, independent and healthy. Commissioning services at a local level to meet the needs of the local population will give confidence that there will be enough capacity in services to meet local demand.

- Integrated data for decision making is a fundamental feature of successful health and social care systems. Whenever an individual moves between a health and care setting, it’s important that the full picture of that individual’s health and care needs are made available to help make truly informed care decisions. Removing barriers for staff to see records from across organisations make it easier to work collaboratively and build trust across the system. Shared care records, accessible data infrastructure and the Covid-19 COPI legislation are critical enablers to this end. Despite this, the latest Covid-19 COPI legislation extension is due to expire at the end of September which would be a move in the opposite direction.6

- Coordinated discharge planning should start as soon as a person is admitted to hospital with the Discharge to Assess and Home First models fully implemented. There should be regular reviews of decisions made to ensure that they are embedded, working effectively and suitably empowering patient choice.

- Leadership at a place and ICS level is required to make these things happen in practice and to properly hear all the voices from the health and care system to advocate for the services required for local communities. Commissioning and funding mechanisms need to be aligned to incentivise systems and providers to support people at home. There is an opportunity for the upcoming white paper on social care reform to provide a framework, with the Better Care Fund providing an interim funding mechanism, to support transformation of services in the community and within wider systems.

Transforming social care will be a difficult journey for many systems facing a range of workforce and structural challenges with their care provision, but there is a large opportunity to improve the numbers of people receiving care at home, within the current system. The social care system that entered the pandemic was underfunded, understaffed, undervalued and at risk of collapse5. The health and social care white paper and the anticipated funding reform, provides an opportunity to put the care sector on a more sustainable footing, to work towards resolving the service variation across geographies and to addressing the longstanding social care challenges exacerbated by Covid-19.

Read the full IPPR report here.

References

[1] The Report of the Commission on Funding of Care and Support, July 2011, A Dilnot et al. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130221121529mp_/https://www.wp.dh.gov.uk/carecommission/files/2011/07/Fairer-Care-Funding-Report.pdf

[2] Social care 360, The King’s Fund, May 2020, S. Bottery et al. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/Social%20care%20360%202020%20PDF_0.pdf

[3] Key facts and figures about adult social care, updated July 2021, The Kings Fund, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/key-facts-figures-adult-social-care

[4] Overview of the UK population: January 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/january2021#the-uks-population-is-ageing

[5] Adult social care and COVID-19: Assessing the policy response in England so far. The Health Foundation, July 2020, P Dunn et al. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/adult-social-care-and-Covid-19-assessing-the-policy-response-in-england

[6] Coronavirus (COVID-19): notice under regulation 3(4) of the Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 – NHS Digital. Update Feb 2021, On behalf of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-Covid-19-notification-of-data-controllers-to-share-information/coronavirus-Covid-19-notice-under-regulation-34-of-the-health-service-control-of-patient-information-regulations-2002-nhs-digital

[7] NHS England ‘Home First’ approach, https://www.england.nhs.uk/urgent-emergency-care/reducing-length-of-stay/reducing-long-term-stays/home-first/

[8] United Kingdom Homecare Association, The professional association for homecare providers and a 2012 survey of a sample of 11,700 people by Saga / Populus. https://www.ukhca.co.uk/mediastatement_information.aspx?releaseID=231933

[9] Reablement – A review of evidence and example models of delivery, NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group, December 2014 https://www.doncasterccg.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Reablement-review-FINAL.pdf