Summary

The tremendous challenge of COVID-19 has been met with extraordinary effort, by the life science industry and its research and health service partners. This response has been global in scale and spans discovery, development, and commercialisation. It has resulted in fast-tracking clinical trials and regulatory processes, which have achieved in less than 12 months what conventionally takes more than ten years, in the case of vaccines. Shared ambition and aligned incentives have enabled health systems and the life sciences industry to work collaboratively in developing vaccines that will bring the pandemic to an end. The urgency in finding vaccines and therapeutics, and the scale of the impact of COVID-19 have made governments and pharma less risk-averse in their decisions and has led to a paradigm shift in their relationship, offering the opportunity for permanent and beneficial change in the long term.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the largest health crises in recent history, unparalleled in recent memory and rivalled only by the Spanish Flu of 1917. The impact of the virus has been felt dramatically in healthcare, but has also had extensive economic and social implications. Indeed, the pandemic has completely transformed the way we go about our daily lives, from work and travel to social interactions.

The scale and magnitude of this pandemic have made finding vaccines and therapeutics a global priority for governments. An unprecedented collaboration between the life sciences industry, the research communities and health systems has been underway since early 2020 and has led to the discovery of new indications for existing drugs and what appear to be highly effective vaccines.

A number of vaccines have been able to reach Phase III of their trials in record time, with three of the leading candidates, Pfizer/BioNTech/Fosun Pharma, University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines, and Moderna/NIAID, anticipated to gain regulatory approval and to begin roll out by the end of 2020. The typical time for developing a vaccine is at least ten years, so, how has it been possible for the development of these COVID candidate vaccines to have progressed this quickly? In this article, we explore the innovative research and regulatory processes that have enabled these breakthroughs, which hold the potential to bring the pandemic to an end and to reshape the relationships between pharmaceutical companies and health systems.

A massive global effort

The publication of the genetic sequence of COVID-19 in early January 2020 triggered the mobilisation of an international response to find a vaccine. By March, four candidate vaccines had already entered human evaluation, and by April there were nearly a hundred candidate vaccine being geared up for development. At the time of writing of this article, more than two hundred vaccine candidates are at various stages of the testing process. According to the World Health Organization (12 November), 48 candidate vaccines are in clinical evaluation and 164 in preclinical evaluation.[1]

This global effort is not only remarkable for its sheer magnitude, but also for the unprecedented collaborations and alliances that have been formed between life sciences companies, research institutes, health systems, and international health organisations. The COVID-19 pandemic has created a unique set of circumstances in which the incentives for all the partners have been aligned, and where all of them gain from the successful development of a vaccine.

Two mechanisms of action

Two very distinct types of vaccine – viral vector and messenger RNA – currently lead the field in the fight against COVID-19.

Viral vector

A vector vaccine works by using a different and harmless virus as a platform or vector to transport pieces of the COVID-19 protein into the body in order to stimulate an immune response. [2]

The vaccine being developed by the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca uses this mechanism, replicating the genes for the spike protein on the surface of the COVID-19 virus, using a harmless virus as the carrier. Once it enters the cells, it starts to produce the COVID-19 spike protein which triggers the immune system to produce antibodies and activate killer T-cells to destroy infected cells. If the individual is exposed to COVID-19 again, the antibodies and T-cells are stimulated to fight it. [3]

Messenger RNA

A messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine inserts fragments of genetic material – mRNA – which encode the viral protein, into human cells. In this way, the body gets a ‘preview’ of what the real virus looks like without causing the disease, giving the immune system time to produce antibodies that can fight the real virus if it is encountered. While the mRNA vaccine technology has speed and cost advantages compared to traditional protein vaccines, as well as increased cellular immunity, however, the instability of the mRNA molecule means that it requires cold chain distribution and low temperature storage. [4]

The vaccines developed by both Moderna/NIAID and Pfizer/BioNTech/Fosun Pharma use this innovative mechanism. No mRNA vaccine has so far been approved for human use. However, early Phase III trial results for both of these vaccines have now been released, both reporting nearly 95 percent effectiveness,[5][6] and are awaiting emergency use authorisation.

Fast-tracking the trial process

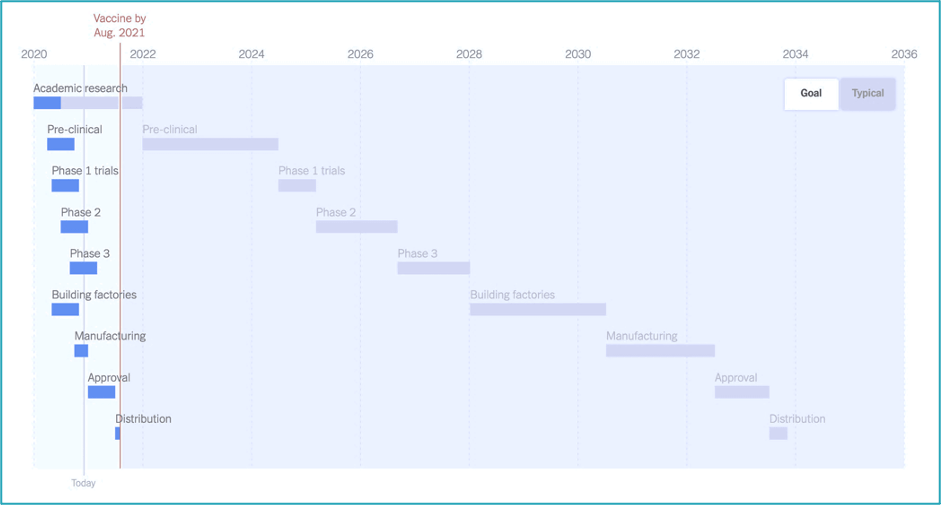

Traditionally, the vaccine development process can take more than ten years from research to approval and distribution. However, the expectation for the timeline of development of the COVID-19 vaccine was set at 12 to 18 months, from the beginning of 2020. While this goal was immensely stretching when compared to a typical vaccine timeline (see figure below), a number of companies were able to reach their Phase III trials in record time, with others following quickly. So, what is it about the circumstances of this pandemic that has made this possible?

The WHO’s position is that in order to accelerate the vaccine development process, development steps need to be done in parallel, wherever possible, instead of in sequence, while keeping in place all the necessary safety and efficacy monitoring mechanisms such as adverse event surveillance, safety data monitoring, and long-term follow–up. Phase IV post-marketing surveillance remains a critical and essential step for identifying side-effects.[2]

In May 2020, the WHO announced the launch of the ‘Solidarity vaccine trial’, a coordinated international, concurrent randomised controlled Phase III trial of different vaccine candidates. A trial at several sites at once will help speed evaluation and ensure that vaccines will have been tested in different populations. This trial allows to:

- Evaluate several different candidate vaccines, which increases the likelihood of finding several effective vaccines

- Enrol people expeditiously at sites with high rates of COVID-19, which results in rapid accumulation of data to support rigorous evaluation

- Optimise the design and conduct of separate trials, with results available within 3-6 months after each vaccine is ready for inclusion

- Form international collaborations and obtain country commitments to pay, fostering international deployment with equity of access

Regulatory fast-tracking

The commitment by regulators to fast track candidates is an essential component in securing rapid access to successful vaccines and in reducing the risk, to companies and governments, in entering into substantial commitments to pay. Regulators around the world, including the in the UK, are fast-tracking approval processes.[8]

An innovative approach to data collection is a critical element of this. Collection has been adopted, in which information is released during the development process, rather than in a single submission at the end. This approach helps speed up the process, offering increased transparency, without compromising the safety and quality of the data, and enables registration.

Enthusiasm to participate in the trials

A strong sense of public duty, a common goal, and a concern to bring the COVID-19 pandemic to an end have led to widespread enthusiasm on the part of the public to participate in clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines.[9,10] This has been particularly important for the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca and others who have had to move their trials from Europe to Brazil and the US due to a reduction in infection rates in Europe over the summer.

Commercial innovation

The commitments to buy millions of doses of the leading vaccine candidates by governments around the world has helped companies manage the risk associated with the development costs of their products.[11] At the same time, governments can be confident that the substantial resources they are earmarking will be applied to effective interventions because money will only change hands if the vaccines work. The UK alone has already secured early access to 350 million vaccine doses from six different vaccine candidates, making it the world’s highest per capita buyer with around 5 doses for each citizen.[12]

The risk appetites of industry and governments appear to have changed. Life sciences companies are investing considerable funds on the development of vaccines that conventionally have a low chance of succeeding (around 7% of vaccines in preclinical studies and 20% of those in clinical trials[2]). Similarly, the NHS and other health systems would not normally make large advance commitments to purchase a vaccine that is so early in development, or on infrastructure to store and distribute the product (such as storing in -70°C temperature). It is the urgency and scale of the impact of the pandemic that have led the life sciences industry and health systems to become less risk-averse in their decisions.

While the specific details of these purchasing deals between countries and life sciences companies have not been made clear, state commitments on volumes are very likely linked to conditional achievement of efficacy and safety thresholds. Additionally, responsible pricing during and after the pandemic would have likely been a condition of these agreements.

A paradigm shift

Conventionally, it is health systems and those who work for them, rather than the life sciences industry, that the public regard as the heroes in confronting major health challenges. Life sciences companies are not infrequently cast as the villain of the piece, appearing to make money out of the people’s distress. Now, however, these dynamics may have changed. The COVID-19 virus is regarded as the common enemy, with both the health system and the life sciences jointly seem as heroes and saviours. Life sciences companies are benefiting from a surge of goodwill from a grateful public. The question is, can the industry capitalise on that boost to its reputation and draw on the lessons of the pandemic to forge a more effective partnership with its customers, both to improve business as usual and to help it mobilise quickly when the world is again faced with a global health crisis?

About the authors

Ben Richardson is a co-founder and Managing Partner at CF where he leads CF’s work in Life Sciences and Data Science & Analytics. Prior to joining CF Ben was a Partner at McKinsey & Company. He has worked across all aspects of health and care systems and for life sciences companies in the UK and around the world.

Scott Bentley is a Senior Manager at CF in Life Sciences. He has worked extensively with the health and care systems of the UK and Life Sciences companies. Prior to joining CF, Scott worked at ZS Associates.

Sir Andrew Dillon is an advisor to CF. He has held a number of senior management positions in the NHS. He was appointed as the Founding Chief Executive of NICE, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in 1999, a post he held until he stepped down in 2020. He now works as an independent healthcare advisor.

Laurent Abuaf is an advisor to CF. He is a senior executive with more than 16 years of experience in pharma leading local and regional businesses across Europe and Asia. Laurent spent 4 years at BCG Paris and worked on a wide diversity of industries. He was the Country President for AstraZeneca in the UK for 2 years until stepping down in 2020 to become an independent advisor.

Nour Mohanna is an associate at CF who has worked on health transformation, Life Sciences and thought leadership. Nour has a background in behavioural science.

[1] World Health Organization, Draft landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines (12 November 2020): https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines

[2] World Health Organization, What we know about COVID-19 vaccine development: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/risk-comms-updates/update37-vaccine-development.pdf?sfvrsn=2581e994_6

[3] BBC News, Covid: Oxford vaccine shows ‘encouraging’ immune response in older adults: https://www.bbc.com/news/health-54993652

[4] The Conversation, How mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna work, why they’re a breakthrough and why they need to be kept so cold: https://theconversation.com/how-mrna-vaccines-from-pfizer-and-moderna-work-why-theyre-a-breakthrough-and-why-they-need-to-be-kept-so-cold-150238

[5] The New York Times, Pfizer’s Early Data Shows Vaccine Is More Than 90% Effective: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/09/health/covid-vaccine-pfizer.html

[6] The New York times, Early data show Moderna’s coronavirus vaccine is 94.5% effective: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/16/health/Covid-moderna-vaccine.html

[7] The New York Times, How long will a vaccine really take? https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/30/opinion/coronavirus-covid-vaccine.html

[8] Financial Times, UK to fast-track COVID-10 vaccine approval if sought before end of Brexit transition: https://www.ft.com/content/36576d82-b646-429d-b43d-e5be3320eaa5

[9] National Geographic, Oxford vaccine enters final phase of COVID-19 trials. Here’s what’s happening now: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/07/oxford-vaccine-enters-final-phase-of-covid-19-trials-in-brazil-cvd/

[10] Gov.uk, 10,000 UK volunteers to take part in new COVID-19 vaccine trials: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/10000-uk-volunteers-to-take-part-in-new-covid-19-vaccine-trials

[11] BMJ, COVID-19: Pre-purchasing vaccine – sensible or selfish: https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3226

[12] Politics Home, Downing Street Has Defended Its Failure To Pre-Order A New ‘94.5% Effective’ Covid-19 Vaccine And Said The UK Could Get It By Spring: https://www.politicshome.com/news/article/uk-moderna-covid-vaccine