In November 2017, I wrote an article that reflected my frustration about hospital discharge and a concept that health and care systems focussed on, but which in my view was doing harm to patients, staff and systems: delayed transfers of care, or DToC.

DToC was a classification that was applied to patients who were medically fit to leave an acute hospital and had been declared ready to leave by an MDT. Its purpose was to create a mechanism whereby local authorities could be fined by healthcare providers for the care they were providing to a group of patients who didn't need to be in hospital. The process didn't encourage different parts of the health and care system to work together and resulted in undue focus being placed on one subset of people who were ready to leave hospital, masking the scale of the challenge. For every patient classed as a DToC, another three were medically fit to leave their setting of care.

Keeping people in hospital is not a neutral act

The most important part of the article for me was it called out that keeping people in hospital who don't need to be there is not a neutral act. Hospital stays in frail older people, many of whom have complex needs, decrease mobility, reduce independence increase the risk of falls and infections, and can bring on delirium or worsen dementia. There is a long-term impact of this physical and psychological deconditioning on the quality of people's lives. We worry about the risk of discharge from an acute setting but tend to play down or even ignore the risk of not doing so, despite the fact that more appropriate care can be delivered with better outcomes away from the acute setting, frequently at lower cost.

Seven years on, what has changed?

The term Delayed Transfer of Care has been dropped – it was one of a range of measures that were shelved during the covid pandemic, when business intelligence capacity was required to help manage acute sector capacity effectively. A new classification was introduced and captured as part of SitRep data from the winter of 2020 – the discharge ready date or 'no criteria to reside'. NHSE has set out a list of criteria that mean continuing an inpatient stay may be appropriate; the number of patients who do not meet the criteria to reside is captured daily, along with the number of these who are actually discharged.

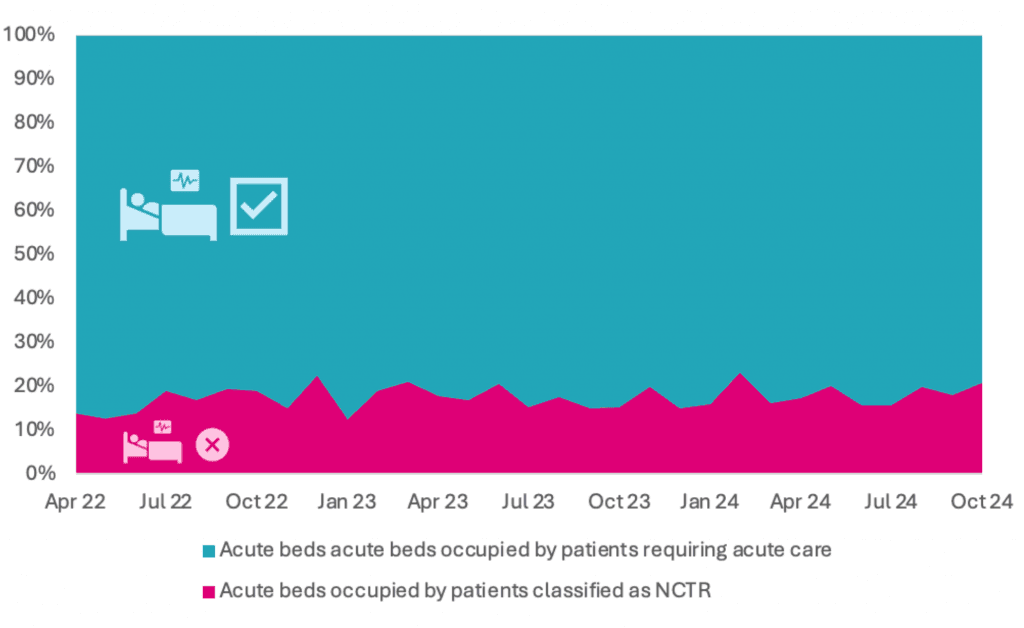

The result of this change in recording is that there is now a much clearer understanding of how hospital beds are being used by patients whose care could, with the right health and care services, be delivered elsewhere. From the perspective of hospitals and systems, there is visibility of the proportion of hospital beds that are effectively not available for the delivery of acute care. From the patient perspective, we can see how long people are being kept in a care setting that at best doesn't meet their needs, and at worst is impacting their longer-term quality of life.

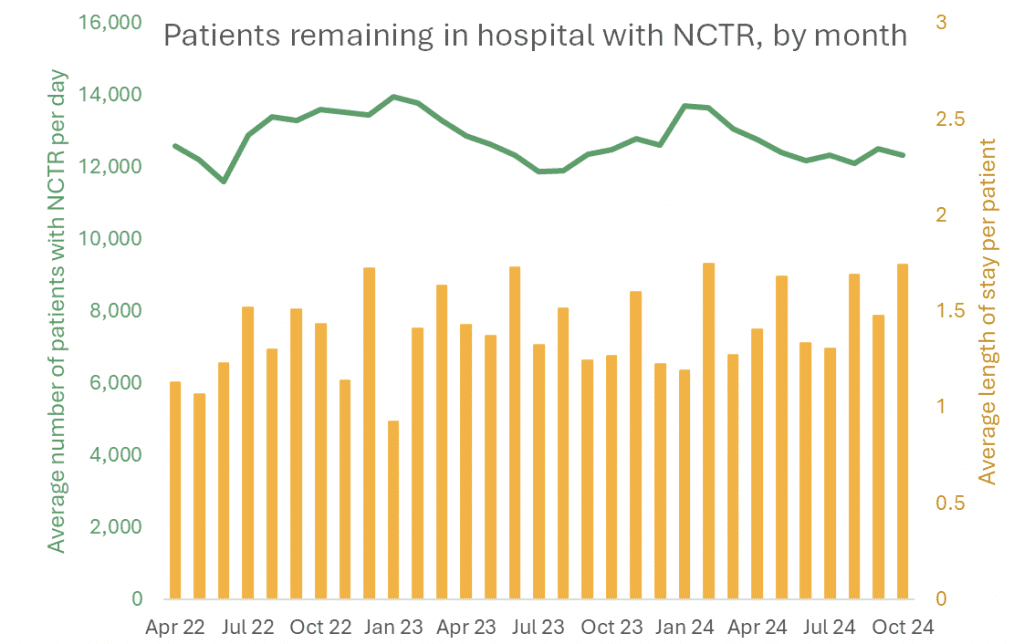

The figures are significant: 13.0% of general and acute beds in October were occupied by patients who no longer needed to be cared for in an acute setting, or over 12 000 people who are not getting the most appropriate care for their needs every day.

What is harder to determine is how long patients are remaining in hospital beyond when they are clinically ready to leave. Sequential data snapshots don't allow the tracking of patients to determine what proportion of their total stay in hospital was needed to meet their clinical requirements. What is reported is the total number of people who were classed as having no criteria to reside during their stay. In October, 83% of patients in this category had a total stay of more than 14 days. This suggests patients are having prolonged unwarranted stays in hospital with all the risk that entails.

What is driving delays in hospital discharge?

From May 2024, an additional layer of information has been added with a weekly submission from every acute provider setting out the reasons for patients with a total length of stay of 14 days or more, across the whole discharge pathway. For this cohort the detail is helpful, but the categories are still relatively broad; the data isn't suitable for taking commissioning decisions, for example about the type of bed-based care a system needs to have in place. However, common themes emerge when working with providers and systems.

Capacity in the services needed to support someone on discharge are a common challenge, whether that is community health services, intermediate care or social care. Funding solutions have frequently been short term, which doesn't support the commissioning and delivery of best practice. The hospital discharge pathway itself can be complex, with bottlenecks in assessment across settings and professional groups. The number of data points now captured reflects this complexity, and is why auditing every delayed patient weekly, rather than just those with a length of stay of more than 14 days, isn't being undertaken. Finally, patient needs have changed – admitted patients, especially those admitted as an emergency, and getting older and have more complex needs both when in hospital and when they are ready to go.

Moving from diagnosis to treatment

While the language and available data have changed, the challenge remains: from a system perspective we are locked in a pattern of keeping people in hospital beds unnecessarily, which is both harming them and other people whose admission to hospital is delayed. The ongoing consequence of this from a system perspective is rising demand for social care including residential care, some of which could have been avoided by earlier discharge. For individuals, it's a reduction in their function, their independence and their quality of life. We must view delays in discharge as avoidable harm and treat it as we would a drug administration error or a pressure sore.

Addressing this challenge will not be easy – ingrained habits are difficult to break and getting patients who no longer need care in an acute hospital into the right setting for their needs has been a struggle for a long time – since well before we fully understood the full impact of not doing so.

So, what is needed?

- Collective alignment on this issue as a priority is critical. This requires a compelling, evidence -based 'case for change' that resonates with everyone who is involved.

- A single version of the current position at ICB and provider level is needed, so that improvement opportunities can be defined, sized and prioritised

- There must be a granular description of what people need to do differently to deliver their part of a process that creates a different outcome

- The enablers that allow all parties to operate effectively with a common purpose need to be put in place – this includes shared data and common leadership

- A process for tracking progress that includes a route of escalation when barriers are met is needed, built on metrics that resonate with people, so they can see tangible progress being made.

Given the scale of the change we need to make, addressing this is going to take time and commitment to seeing the work through. The potential benefits are enormous, for systems and organisations, but most importantly for the people who, every day, are spending time in a hospital bed that is harming them.

To find out more about this article, or to speak to one of our specialists about improving health systems to transform service delivery, get in touch today.